Show NotesQuestions for Reflection

Each episode we offer you a few prompts to think about how that day's conversation applies to you. Our supporters over at Buy Me a Coffee now have exclusive access to the PDF versions of all our Questions for Reflection. Join us today!

Transcript

Beth Demme (00:03):

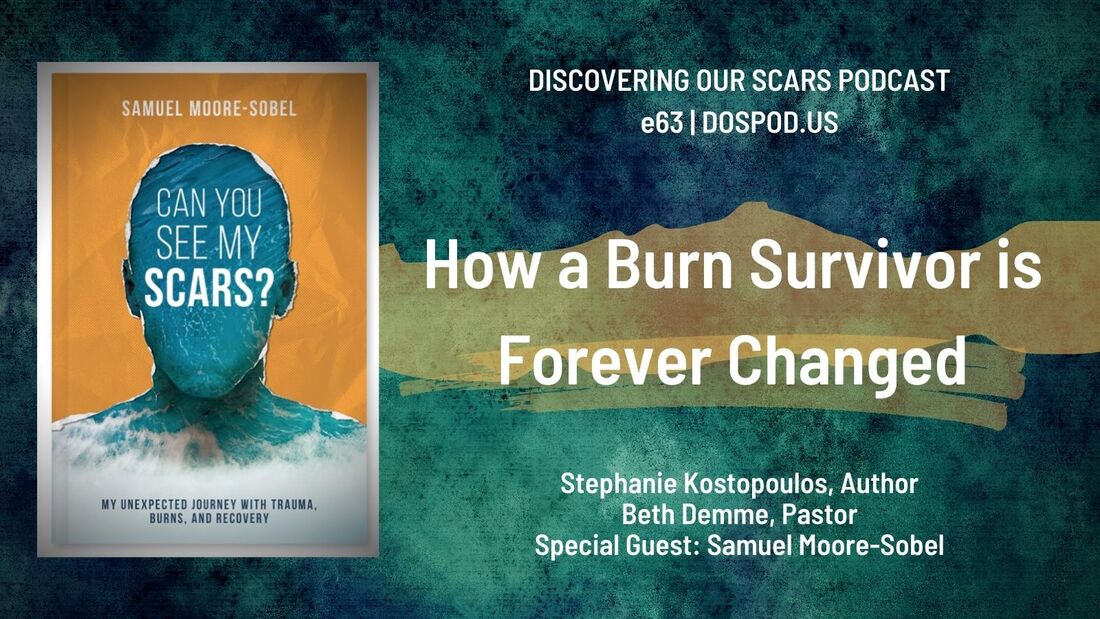

Welcome to the Discovering Our Scars Podcast. Stephanie Kostopoulos (00:05): Where we have honest conversations about things that make us different. Beth Demme (00:08): Our mission is to talk about things that you might relate to, but that you don't hear being discussed in other places. Stephanie Kostopoulos (00:13): Our hope is that you're encouraged to have honest conversations with people in your own life. I'm Steph. Beth Demme (00:17): And I'm Beth. On today's show, we're going to have an honest conversation titled How a Burn Survivor is Forever Changed with Samuel. Stephanie Kostopoulos (00:25): Then we'll share a slice of life and the show will close with Questions for Reflection, where we will invite you to reflect on the conversation in your own life. Beth Demme (00:33): Well, good morning, Samuel. Welcome to the Discovering Our Scars Podcast. It's nice to have you here with us, virtually. Samuel Moore-Sobel(00:40): Thank you so much for having me. It's an honor to be here. Beth Demme (00:43): So we're in Tallahassee, Florida, but you're not here in Florida. Where are you? Samuel Moore-Sobel(00:48): I am in Northern Virginia, just outside of Washington, D.C. Beth Demme (00:52): Awesome. And you're the author of a book called Can You See My Scars? This is your memoir, right? Samuel Moore-Sobel(00:58): That's right. I just published the memoir on September 1st of 2020, so just a few months ago. Beth Demme (01:04): So, why don't you introduce yourself to our listeners? Samuel Moore-Sobel(01:07): Absolutely. Like you've said, my name is Samuel Moore-Sobel. I live just outside of Washington D.C., and work in the tech industry by day, but wrote a memoir called Can You See My Scars? that I published just a few months ago, which talks about my journey as a burn survivor. And not only the accident itself, but what it took to heal and, hopefully, in an effort to inspire readers and others on their journey as they face adversity in their own lives. Stephanie Kostopoulos (01:34): That was awesome by the way. First of all, I got to say, that was the perfect elevator pitch. So, bravo. I got to say, when I heard the title of your book, I was very intrigued, because I was like, "Well first of all, that's exactly what we talk about." That's something that I have a lot of personal experience with. So we are really excited to dig into all of that today. Stephanie Kostopoulos (01:55): And I do want to point out that Beth has actually read your book and she said it is fantastic. I chose not to read it yet, but, literally after this, I'm going to read it. Because I thought, if we both had read it, we might talk about stuff that we don't explain to the listening audience. So, I'm going to be the person that hasn't read it and then after I'm going to read it. But I want to dig right in and I want to know, how did you get burned? Samuel Moore-Sobel(02:19): Yeah, it's a little bit of a complicated story but I'll try to distill it here to a soundbite. But, basically, I was hired for a day to move boxes and furniture. I was a week away from starting my sophomore year of high school and I was eager to fit one last odd job in before the summer ended. And I had been doing a bunch odd jobs in the community all summer, and was hired by someone who just lived a few blocks from my parents, in the same community, who needed some help moving. Samuel Moore-Sobel(02:45): Upon arrival in the job scene, things changed really quickly and kind of the details started to change. At the time, I kind of chalked it up to maybe I had misunderstood the original intent or the original plan, but it was kind of a common theme throughout the day that things would change. So, upon arrival at the site, I was told that, actually, we were going to be taking things from the storage unit, bringing it back to his home. And then from there, we would be taking whatever was left over, that he wasn't able to house in his garage, to a friend's house nearby. Samuel Moore-Sobel(03:15): As the day goes through, it's getting kind of longer and longer, we're now past time. My dad actually calls me and says, "I think it's time for you to go home." And as we're having this conversation, the man overhears and says, "Oh, my friend's house is just a few minutes down the road," and so that assuages me and my dad and I agree to go with him in the truck. And as we're driving the U-Haul, 5 to 10 minutes actually turns into over 45 minutes, and we've passed county lines, and I don't recognize where we are, and I don't know what's happening. Samuel Moore-Sobel(03:48): Keep in mind, I'm 15 years old, so even more befuddled by what's happening. And we ended up going up to this gravel road to get to this house at the top of a hill, and he says he's going to back the truck down to the bottom of the hill where there's this shed, where we're going to house everything from the U-Haul truck and put it in there. But, upon getting to the bottom of the hill, we're introduced to his friend, who's the homeowner, and she opens the shed doors and it's just filled with stuff. And so, we're told, "Oh no, now you're going to have to empty the shed," before we could get the man's stuff in the shed. Samuel Moore-Sobel(04:23): So, just a comedy of errors in some ways. Kind of taking stuff out of the shed. Eventually, a box makes its way to my hands. It's the very first box that comes my way and the homeowner says, "Toss it." And I looked down in the box and there's books and there's hay. And when I say hay, it's literally straw protruding from this box. It's open, there's no tape. It's just this normal cardboard moving box. And I think, "This is kind of an odd assortment of items, but who am I to judge what people have in their sheds?" And just follow the instruction of "Toss it," like she said. But the second that it gets tossed onto this cement slab nearby, there was an explosion that rings out. And I see this substance come flying towards me, I don't know what it is. I closed my eyes, thankfully, and I just feel this substance hit my face and it's just immediately pain. Samuel Moore-Sobel(05:14): I mean, it felt like somebody had lit me on fire, it just felt like I had walked into a burning building. And I wasn't sure what was happening, and I'm in the middle of nowhere, and I feel like this might be the end of my life, this might be it. Stephanie Kostopoulos (05:27): Whoa. Okay, I have questions. First of all, did it get on anyone else? Samuel Moore-Sobel(05:32): It did not, it was just me. Stephanie Kostopoulos (05:35): And what was the substance? Samuel Moore-Sobel(05:35): So, eventually, I find out that ... Once the ambulance arrives and they put me on a stretcher and put me into the ambulance, I overhear the paramedics talking about how they had asked the homeowner, the woman, for the substance or what the substance was. Apparently, it was a glass jar of sulfuric acid that was stored at the bottom of this box, under the books and hay, and it exploded. Samuel Moore-Sobel(06:00): Another aspect of this was, because it was exposed to the elements in the shed, it was a little bit more highly charged than it would have been normally. So the doctors had told me, "You know, it should have just hit your legs. But because it was exposed to the elements in this way, it hit your face." And I'm six-feet-tall and the slab was a few feet away, so it came quite a ways to burn my face and arms. And I suffered second- and third-degree burns as a result. Stephanie Kostopoulos (06:24): And why did she have that? Samuel Moore-Sobel(06:24): Sure. The homeowner told the authorities that apparently it belonged to her ex husband. That he used it for metal etching and that was her explanation for why it was there, stored in the bottom of the box. But, ultimately, I don't really know the reason why it was there. And I spent a lot of time trying to figure that out and haven't really come to an answer all these years later. But that was kind of the explanation that she gave to the authorities. Stephanie Kostopoulos (06:45): Was there any legal ramifications? I feel like- Samuel Moore-Sobel(06:48): So that was kind of the interesting part about this journey, as well. So, going through the legal system felt like ... Because my parents had contacted the authorities and kind of went up the chain and they were kicked around from county to county and locality to locality, and eventually nothing could be done because apparently the county where it had happened didn't have a Fire Marshal and so, that was kind of the linchpin here. If it had happened one county over or, really, up, down, left, right, east, west, north, south, there would have been more consequences. But because of that, there were no criminal charges that were drawn up against her. Samuel Moore-Sobel(07:22): Also, OSHA had done an investigation, and I write a little about this in the book, but they did a long-standing investigation. In the end, said that there was nothing they could do either because I had been listed in my community newsletter as available to work and because of it, that was considered advertising, quote unquote, and therefore there was nothing that they could do there either from a legal perspective. So, it was kind of a frustrating ... At the time, for a long time, I felt like ... I don't feel this way as much anymore, but for a long time I really failed by the system and I felt like you're told that there's laws in place for a reason and that when bad things happen, that people will be held accountable. And that really wasn't the case in this situation. And that was really frustrating as a teenager and growing into young adulthood, that not more was done. That you could just literally have a glass jar of sulfuric acid negligently stored and nobody cares, and that was really a tough thing to swallow. Beth Demme (08:18): There were a couple of times, reading the book, and I really do like the book and I really do think everyone should read it, and if you're ... This episode will come out in advance of Christmas, and if you're somebody who likes to buy books for friends and family to read, this is one I would recommend, because it's a really compelling story and you've written it really well. One of the things that was frustrating reading it though, was this unresolved concern that I felt about people not being held responsible for how they were negligent. And then it occurred to me that, as unsatisfying as that is as a reader, wow, that's your life. So, I mean, it's just a reflection of the reality of "Yeah, this is really disappointing." Stephanie Kostopoulos (08:58): Well, and you're also a lawyer. So did you also have that- Beth Demme (09:02): Yes. Stephanie Kostopoulos (09:02): ... annoyance, that you know the law and you know everything- Beth Demme (09:05): Yes. Stephanie Kostopoulos (09:05): ... and just ... Yeah? Beth Demme (09:07): Yeah. I won't make you talk about it, because I'm sure that if there was one, it remained confidential, but surely there was a civil suit. But you don't have to talk about it, I don't want to make you say some things you shouldn't say. There were certainly grounds for a civil suit, I'll say that. And anybody with homeowners' insurance has liability coverage. Beth Demme (09:22): So, anyway. Let's go back to that day that you were burned, because one of the things that you describe in the book, that has really stayed with me is, after it happens, in the moments after it happens, it felt to me, reading it, like you were on your own. I mean, you're 15, you're there with these two adults who have put you in this position, and a friend who you had kind of recruited to help with the job. So, there's a couple of teenagers and a couple of adults. And I can understand your friend not being equipped to help you, because what does a 15-year-old know in a stressful situation like that? But the adults really let you down. Beth Demme (10:01): I mean, from the beginning, they didn't immediately rush to your aid, or immediately call 911, or try to fix this problem that they had created. So, can you kind of describe that for us? As soon as the substance gets on you, they don't immediately call 911, right? Samuel Moore-Sobel(10:21): Yeah, exactly. Yeah, that's a great point. This is happening, and I'm in a ton of pain and going into shock and having trouble kind of comprehending anything that's happening around me. But, in that moment, there was ... My friend is basically asking the man who had hired me to call 911. Which is kind of frightening, that he doesn't want to do it and he seems really hesitant. It's almost like this surreal moment where you're like, "Is this really happening right now? Is he not going to call the authorities?" And so, eventually, he's able to get him to do that. I think at one point he even described ... We talked about it later and he kind of grabbed the man's phone and was like, "Call 911." Samuel Moore-Sobel(11:07): So, finally, he does that. The man is on the phone with 911, leads me up the hill, and they ask him, "Hey, what is the substance?" and he can't answer the question. And so he says, "Oh, I'll go back down the hill and find out," and he hands me the phone and says, "Here, talk to this person." Samuel Moore-Sobel(11:25): And so, I'm on the phone with the 911 operator at the top of this hill, alone, for much of the first several minutes of this, and he's off doing whatever. And the 911 operator is kind of reiterating the need for water and having somebody pour water on my face, that I couldn't do it myself because I could put it back into my eyes or cause further damage. But he and everyone else was nowhere to be found, and that was really frustrating. Samuel Moore-Sobel(11:47): At one point, actually, the homeowner shows up with a bucket of water but it's warm water and the 911 operator kind of overhears this, we're relaying this, and says, "No, no, that'll scald you." And so we end up ... She says, "Oh well, I tried," and walks away. And so, I'm at the top of this hill, nobody's there, nobody cares. I feel like I've done [inaudible 00:12:10]. It starts this ... It's interesting how these things can start in your brain. And the feeling I had was "Maybe this isn't that bad." And it was kind of something that was reiterated throughout this experience, when people would minimize it or said I looked great, it didn't matter. And so, I'm starting to think "Man, am I crazy? Maybe there's something wrong with me or I have low pain tolerance," or, "Maybe this shouldn't be hurting so much." Samuel Moore-Sobel(12:30): I mean, it cast such doubt in my mind as a 15 year old boy, who's seeing all these other adults who ... I had grown up in this home where you respected elders, you respected authority, and these people were in authority and I thought, "Well, maybe they know better than me and there's something wrong with me." And so, that was really hard to grapple with. And I did, I felt utterly alone and I thought I was going to die on that hill and that that was going to be the end of my life. And I was really pleading and praying that that wasn't going to happen, but I thought, "This is going to be the end." Stephanie Kostopoulos (12:59): Wow. You hadn't seen yourself, so you didn't know how bad it was. You just could feel it, correct? Samuel Moore-Sobel(13:06): Exactly. Yeah, I hadn't seen myself yet. Stephanie Kostopoulos (13:10): When were you able to see yourself, to see actually what the damage looked like? Samuel Moore-Sobel(13:15): Yeah. So, I saw myself for the first time ... By the time I got to the hospital, they stripped me naked, they threw me in a chemical shower and then, eventually, I get taken back to a room and they're telling me they're going to medevac me to another hospital that is better able to handle my case. But before they do, I'm sitting there and I'm having a conversation, and the man has arrived and he's asking me questions and saying insensitive things. And, at one point, it comes up that I hadn't seen myself yet, and a nurse nearby overhears that and says, "Oh well, do you want to have a look?" And before I can answer yes or no, throws a mirror into my lap and I kind of pull that mirror to my face for the first time, and there's no social worker, there's no psychiatrist. It's just me and a mirror. Stephanie Kostopoulos (14:01): No family? Samuel Moore-Sobel(14:02): Yeah, no family. It's just me, dealing with this [crosstalk 00:14:04]. Beth Demme (14:03): Yeah, I couldn't believe that they didn't at least wait for your parents to get there. I mean, I just couldn't believe how many people kind of failed you along the way, and I say that as a complete outsider but also thinking about it as a mother of teenagers. Thinking about my kids and thinking, "If my son took an odd job and this happened to him, I would want to be by his side every step of the way, " and I'm sure that your mother did as well. And so, to think that there was this additional layer of trauma, because they just didn't have the sensitivity to wait a minute. Samuel Moore-Sobel(14:34): Exactly. Beth Demme (14:34): So when you saw it, what did you see? What did you feel? Samuel Moore-Sobel(14:37): Yeah, I totally agree. That's a great point. So when I saw and I just see these large black and brown stains, and it doesn't even look like me. I don't know who this person is in the mirror, and I'm kind of grappling with my newfound appearance, and I can't believe it. I mean, I don't recognize myself, I don't know who this is. And it's just really powerful because it's kind of that first moment where I'm grappling with losing my face and what that means, not just from the appearance but just the trauma and everything that goes along with that emotionally. And it just felt really alone in that moment and I didn't have a way to kind of process that and I didn't know how it would look. And each hour that would pass, and even in the weeks to come, it would change and kind of morph into different colors. Samuel Moore-Sobel(15:24): There's pictures of me where it's green and I kind of look like an alien, almost. My face just contorted into all these colors and, eventually, it evened out to what's there now, which is red marks. But, for a while, there was a lot of changes in that and it just didn't look like me. And one of my eyebrows was almost burned off, you could push the skin back and forth. My face just looked irrecognizable and I just didn't know who I was. Stephanie Kostopoulos (15:53): And in that moment, because you had said before, when you were on that hill all alone, you said, "You know, maybe it's not that bad. These adults are acting like it's normal." In that moment, when you actually saw your face, did you realize how bad it was? Were you angry at the adults for not taking more action? Samuel Moore-Sobel(16:13): Yeah, it definitely became more real. I thought, "Wow, this is more damaging than I thought." But I was really curious too, which I think kind of speaks to maybe me being a teenager or maybe who I was, I wanted to see what the others thought. So, I was kind of eager to see what others thought. Samuel Moore-Sobel(16:28): And it wasn't until I get to the next hospital, that family friends arrive and my parents arrive, and the seriousness of it, when I see the family friend crying, when I see my dad crying, and then I'm asking the family friend, who's holding my hand, "How do I look? How do I look?" and she's telling me, "I'm looking at the inside, not the outside," that that was even in some ways even more powerful to me, to say, "Oh well, other people notice this, other people are seeing this. This must be really bad." Samuel Moore-Sobel(16:56): So, in some ways, it kind of takes me a few more hours to kind of get to that place. But yeah, absolutely, I was starting to kind of get the sense that maybe this was a bigger deal than people had led on. And, of course, I'm thinking, "Well, what's the rest of my life going to look like?" Especially at that age, where you feel like anything that happens is permanent, almost. You don't have the life experience to kind of look back and say, "Hey, things change." I thought, "Well, maybe this is how I'll always look. This is how I'll always feel," and I didn't really see a lot of ways out. Stephanie Kostopoulos (17:25): As you're talking, it's so interesting because there's so many parallels to my story, even though our stories are completely different. But as you're talking about feeling alone, being in the hospital, seeing yourself for the first time, it's reminding me of when I had my incident with self injury, was sent to the ER, was treated like nothing, no one cared. And I remember seeing myself for the first time, just in the mirror. Obviously, didn't have visible scars like you, but I saw my reflection and it was just somebody that had just been dragged through the mud for hours, had no one care about them, had just been treated so horribly. And as you were explaining, I was remembering that. And it's just so interesting how your story is completely different from mine, but how I can completely feel it in different ways. Stephanie Kostopoulos (18:13): I will never know and can fully understand your story and how it feels, but I can kind of have that connection. So, I love hearing people's stories and really hearing about just things that people go through, because we're all connected in different ways and the more we learn about each other, the more that I think we can understand each other. Beth Demme (18:32): I think too, the fact that you were 15 and that's a time in life when, I think part of the human experience is that you're sensitive about your appearance when you're 15, right? Samuel Moore-Sobel(18:41): Mm-hmm (affirmative). Beth Demme (18:41): You're coming into your sophomore year of high school, "These are going to be the best years of your life," people will say. And then you come into those years, as you have said, without your face, right? Samuel Moore-Sobel(18:55): Mm-hmm (affirmative). Beth Demme (18:56): Because of the way that you were burned. So that had to be going through your mind, on some level, right? Like you were saying it, not having the life experience to know, "I'm going to get past this." Samuel Moore-Sobel(19:09): Absolutely. I totally relate to that, as well, Steph. I mean, I think one of the things that's been so powerful about this book and talking to other people, is that we all have scars. They may not be as physical as mine, but we all have emotional scars that we go through, we all have trauma. And one of the things that I've discovered through this journey is that there's a universality to suffering that I think is ... Adversity is the great equalizer and we've all known what it's like to have that happen. Samuel Moore-Sobel(19:38): As I was going through this, you are. You're struggling, when you're 15, to try to ... not only with ... Appearance, I think, has an outside. I mean, I think we always care about our appearance throughout life, but I think that it's very important in high school and I was kind of grappling with "How do I re-enter into ... ?" That was one of the things that I thought about a lot. Samuel Moore-Sobel(20:02): After the accident, I'm on home-bound tutoring, so I don't go back to school like the rest of my sophomore class, a week later. I'm on home-bound tutoring for several months and, eventually, go back in that mid-November. But that was one of the fears I had about going back to school, "Well, how am I going to go back and assimilate back into society," as it were, "because of this?" And I just felt really ill prepared to do that. Samuel Moore-Sobel(20:26): And when I went back, it was ... It did. I definitely felt the distance. I never got bullied by anybody, but I definitely felt like friends and even extended family members and others just kind of drifted away. And they just didn't know what to say and they didn't know how to interact with me, and it felt really lonely. I felt like I'd lost my face, but I lost so many other things too. I felt like I lost the confidence in myself, I felt a lot of shame, I didn't like how I looked, I didn't like how I felt, struggling with my mental health. But then I had all these other relationships that just kind of went away and it just felt really lonely and I just didn't know how I was going to do it. I felt like I had to do it all on my own and I didn't know how I was going to be able to make it through. Stephanie Kostopoulos (21:07): When you were going through that in your high school years, were you ... Every time you were in public, were you self-conscious about your scars? Were you uncomfortable about the scars? Or were you uncomfortable that you were making other people uncomfortable? Were you afraid that you were making other people uncomfortable with your scars? Samuel Moore-Sobel(21:26): Yeah, that's a good point. I think a little bit of both. I think I was really concerned about ... Every time I would be around other people, I felt really concerned about, especially meeting new people, "When are they going to notice? When are they going to notice?" So I remember thinking, in the back of my head, whenever, whoever it was, adult, teenager, whatever age, I would be really concerned about "What is this person thinking?" After it happened enough, I could kind of see in their eyes when they noticed. You can kind of tell, "Oh, they noticed," and then they change. Samuel Moore-Sobel(21:55): They change kind of how they look at you, or they'll kind of zero in, their eyes are kind of focused on that area. Especially the one under my nose seems to be the place that people see the most and especially during those days, out in the chin, but they'd just kind of ... Or they'd ask a question about it. And that was one of the hard things too, I didn't ... I remember kind of going back to school and my guidance counselor kind of talking to me about preparing a short, sweet statement about kind of what happened. And that way, kind of, when I'd get that question ... Because, obviously, this is a hard story to just kind of distill into 30 seconds about the enormity of what had happened when I got questions, but it really took me a really long time to do that. Now I don't have to, I can just say, "Hey, go buy my book and then you can find out more." Beth Demme (22:35): Yeah, that's right. Samuel Moore-Sobel(22:36): But I don't know if I ever came up with that. I mean, I remember I would get asked in elevators, I would get asked and I'd have like 10 seconds to answer this and I'm like, "I was in an accident." So, it was something that I felt really self-conscious about and I catch myself, I do it less now, but when I get nervous around other people, I'll put my hand over my mouth or I'll just kind of put it over my mouth so that ... And it's kind of a subconscious thing, I'll find myself doing it. Samuel Moore-Sobel(23:03): Actually, on my first date with my now wife, a few years ago, she kind of noticed that right away, that I would do that. We were sitting in Starbucks on our first date and I would kind of put my hand over my mouth because I was nervous, I was nervous about what she would think of me. She's this beautiful woman and I feel kind of ashamed with how I look. And even then, I'd come a long way but I still felt that. And so it is. It was something I felt uncomfortable with and I didn't want to make other people feel uncomfortable as well, so it was kind of both. Samuel Moore-Sobel(23:29): And there were some people who wouldn't look at me. I mean, I had extended family members who wouldn't look at me until I grew a beard, and that was really painful. Literally, would not look at my face for years until I'd do that. And then I'd shave the beard and then they wouldn't look at me again, and it was never really talked about. Samuel Moore-Sobel(23:45): There's so many subtle things that can happen in family dynamics, in friend dynamics that aren't really said but I picked up on it. I guess I was maybe a little bit more sensitive to those things than others, but I knew it. I knew what other people were thinking and that was really painful. Beth Demme (23:58): And you mentioned this, that you had to do homeschool with tutors after the accident happened. But one of the things that surprised me is that, initially, you were not in the hospital very long, right? Samuel Moore-Sobel(24:10): Yeah, that's right. It was very quick. In less than 24 hours, they released me and said, "There's nothing else we can do for you. The rest is up to you." Beth Demme (24:16): Isn't that crazy, Steph? You were in the hospital longer than he was. Stephanie Kostopoulos (24:19): Yeah. Beth Demme (24:19): I mean, that's crazy to me because of the severity of your injuries, because they just knew there wasn't anything they could do. But you couldn't go to school because there was an infection risk, right? Samuel Moore-Sobel(24:30): Yeah, exactly. So one of the things, in talking to other burn survivors, that the hospital likely did the wrong thing there. They should have kept me longer and there's more they could have done. Actually, and I don't include this in the book, but we found out that they were actually, as they were doing the one surgery they did for me when I was at the hospital, at Children's Hospital in Washington D.C., they were on the phone with Washington Hospital Center next door, having them talk them through the surgery. So, they literally did not know what they were doing, which is kind of a frightening thing, and admitted that to my parents and I. Samuel Moore-Sobel(25:02): So, probably should have been taken to Washington Hospital Center and things would have been different as well. So, again, one more kind of negligent thing in this. It's not just the authorities, it was also the doctors who let me down and the people who were there, the adults. It was just this compounding thing. So, they definitely did the wrong thing by releasing me so quickly. But yeah, you're right. Samuel Moore-Sobel(25:20): Then there was the concern about the surgery. After surgery, they were trying to do a debriding surgery which is supposed to minimize infection, but they were really concerned about a staph infection. And I went to a doctor after that and he had said, he was an ENT, but he kind of looked up my nose and said, "Oh, you're at risk for staph infection. You need to stay home," and that was a really sad moment for me too. I thought I was going to get to go back to school maybe a week or two late. But after he looked in that and said, "No, you can't," because of the risk of staph infection and being around others, I had to stay home. Much like we're doing now for the coronavirus pandemic but for very different reasons. And so, I kind of feel trained to do this. Samuel Moore-Sobel(26:01): I was kind of like, "Oh, I've been here, I've done this." But I had to do this for a while. And even when I went back to school, I still had to be careful about being around others and kind of felt that kind of distinction of being concerned about infection. And then the other thing I had to be concerned about, walking around these tight hallways with backpacks. If I got hit in the face, especially after surgeries, that that was something that I would have to do too, where I'd have to stay maybe a week longer at home just because of that. If I had done that, then it would have knocked the work that was done and I would have had to go back and do it again. Samuel Moore-Sobel(26:33): And so, that was really hard too because there was the added complication of really being worried, all the time, of somebody hitting my face, especially as I was having a lot of work done and going through surgeries. That was another risk too that I had to be cautious about. Stephanie Kostopoulos (26:47): So, I'm curious. You were talking about when people see you, kind of the thought process, things like that. Do you have advice for if I'm walking down the street and I'm about to meet someone new and they have scars on their face, what's the best way of acknowledging them? Not acknowledging them? What would make you feel the most comfortable? Samuel Moore-Sobel(27:08): I think what I learned through this was just ... I think what was important for others to understand was just to treat me like they would anybody else. I didn't want them to necessarily point out the scars. I think there's a way to do it but I think that, first and foremost, I just needed people to connect with me, to listen to me, to just be there just like they would anywhere else. Don't stare too long at the affected areas. Just treat me like a normal human being. Samuel Moore-Sobel(27:38): For people that I'd known for a long time, I think you have to kind of earn trust with someone before you have those discussions. And I think there was a lot of people, and I talk about it a little bit in the book, who people I'd even known for a long time, who just kind of came up and wanted to share their two cents and just kind of lob out those words and then run away. And that wasn't ... I needed somebody who was going to walk through this with me, I didn't need somebody to just throw their two cents in, what they thought, and then ran away. Samuel Moore-Sobel(28:03): And so, the big thing for people to understand is just be there for others, have empathy, and just be empathetic. But also see that person for more than their scars. We all want to be seen for more than the scars that we have both inside and out, and I think sometimes we can kind of typecast people. That's one of the reasons why, when I went to college, actually, I didn't want to talk about this story anymore because I felt like I was just known as the boy who was burned and that's all there was to me, and there was so much more to me than just that. And I really had to come to peace with that, and I was grateful for the few people in my life who saw me as more than that and were willing to talk about more than just, "Oh, how is ..." my surgeries or my appearance, and all those things. Samuel Moore-Sobel(28:41): So I would just say it's really important for people to just have empathy and treat people with respect and treat them how they would want to be treated, and not just kind of zero in on those affected areas and kind of make it all about the scar. Stephanie Kostopoulos (28:54): That's awesome. So, obviously, I think that's great advice for adults. I'm curious, do kids have a reaction to you, especially early on when the scars were way more noticeable? Samuel Moore-Sobel(29:05): It's interesting, one of the things that I still find even today, kids have ... they do, they have a reaction to it and, in some ways, it's such a beautiful reaction to it. My wife and I were actually with friends, a few months ago, and they have a newborn. Holding her for the first time, the first thing she does is grab those areas, kind of touch the scar under my nose and on my chin. Kids are just fascinated by those areas, and I found that working with special needs children, which I did after the accident. For the first summer after that, I worked in a camp for special needs children, and it was unbelievable to me how many of them would reach out, would talk about it, would ask questions, and it was really beautiful. Samuel Moore-Sobel(29:52): It was something that I felt like they acknowledged it, acknowledged the pain of it, but also in a way were fascinated by it and reached out to it as well. Yeah, it is. And I think it's just the innocence of it. Most of the kids who have done it, they'll say ... I had kids, working in the camp, who'd say, "Oh, who did this to you? I'm going to go get them. I'm going to go ... " It was kind of funny. [inaudible 00:30:13]. There was a repeated refrain of like, "I'm going to go, I'm going to go tell them not to do that." There's such an innocence to it and they want to understand and they want to know. Samuel Moore-Sobel(30:24): I felt like children with special needs, they definitely were drawn to it because ... some of them had scars, so they felt kind of this connection to me, I think, because they felt like, "Hey, you're kind of like us," and that was kind of cool as well. But I feel like there's an innocence to it. There were was certainly well-meaning adults in this, but I feel like there was a lot of times where adults would make it about them. And I guess in my experience, I felt like kids are just more curious and there's an innocence to it, where adults are trying to ... they're thinking about it from their perspective and they want to make themselves feel better in it. And so, they're kind of responding from their experience versus kids are just kind of curious and they just want to know more about it. Stephanie Kostopoulos (31:01): Yeah, and I think it's great the more kids learn about these things as kids, the better adults they're going to be and the more respectful to adults. So yeah, I think that's awesome. Beth Demme (31:11): One of the ways that you describe that in the book is how many people, adults, tried to minimize it, right? They would say, "Oh, it's not as bad as I thought it would be," or one person said, "Was it your brother that got burned?" as if, "I don't see anything. I'm going to pretend ... I'm uncomfortable, so I'm going to pretend like this didn't happen." So, that was interesting to me. How did you deal with that? Samuel Moore-Sobel(31:36): What was sad about it to me is that it happened a lot within the Christian community. I had grown up going to church regularly and raised by parents who were strong believers, and had had that experience. And then, going back to church, church was supposed to be this safe place and somewhere that I felt comfortable, and going to that church was not. It wasn't safe for me. I mean, I had a lot of people who said things, especially in that religious context, that were really hurtful. And people outside of that too. But there were people who I felt like it shook their faith in God, and so they were trying to talk to me in a way that made themselves feel better. And it was almost like they were offended by the scars that I had or by my story, because it was kind of like they were trying to square in their own head, "How could a loving God allow this to happen?" Samuel Moore-Sobel(32:27): Another thing I would say too, I think it also speaks to, even in a larger context, just the culture. I mean, it's so superficial, right? We're focused on how it looks, versus how it feels and the emotional impact and the trauma. And so, I think a lot of people were just really focused on the appearance. And to me, I was always like, "This is so much bigger than my face." I mean, the physical pain was there and I think that was another thing. People would say all sorts of things, I shouldn't have surgery, this is how God wanted me to look. Crazy things that would be said. I have the right to have as much surgery as I want for these areas. They don't know how it feels. It's like having rubber on your face, these scarred areas, even today. Samuel Moore-Sobel(33:02): Again, it's making these assumptions and then saying, "Well, you should just do it this way." And I think that, again, a lot of people were well meaning, but I think it just speaks to the culture where we're so obsessed with looks sometimes, we don't take the time to say, "How did this feel emotionally? How did this affect you in other areas?" Part of why I wrote this book and talk about scars so regularly, is that scars should be seen for all of those things. It's not just a physical appearance and I think that it's just such a deeper meaning than just how it looks. Beth Demme (33:30): There's so much in that theology that I want to unpack with you, because I think so much of that is toxic. One of the things that you write about in the book is that there was someone at church who came up to you and said that, as a family, they had been praying a lot about what had happened to you. You write that this person said, "'Our prayers have led us to believe that this was not your fault,' he then explained that the accident had nothing to do with any sinful actions on my part,'" and then you quote him again, "He says, 'We believe it was due to the sinful actions committed by your parents.'" Beth Demme (34:04): So, it's what you described, someone is trying to square this incident with their own theology. And so, "A good and loving God doesn't let bad things happen to good people. And something bad has happened to you, that must mean you're not a good person. Well, no. It's okay, you're a good person, but apparently your parents have done something sinful and so you have to bear the punishment of that." I probably would have never walked in the doors of a church again, but you didn't have that reaction. So, I'm curious how that didn't drive you away from the church and I'm also curious how your parents reacted to that. Samuel Moore-Sobel(34:44): I think this kind of fits with what a lot of ... There was others who kind of echoed similar statements and I think that there was this rush to kind of blame and assign blame. And I could be wrong, but one of the things that I've kind of talked to others about, and I think he was kind of taking that verse, and I'm going to butcher it, "I, the LORD, your God, am a jealous God and I visit the iniquity of the fathers and the children, into third and fourth generations of those who hate me," and I think it's Deuteronomy. But I think that that's something that's talked about a lot in the church and I think that's where they took that from. But this really sent me on a quest, I had to decide whether I would follow Jesus or follow his people, and I think that was a really important distinction for me to make. I had to decide, where is my faith truly? Samuel Moore-Sobel(35:28): And I think growing up in the church, I kind of relied on the faith of my parents or the faith of others. It was kind of part of that culture that I'd been brought up in, and then I had to make that change. And I was already in the process of that as a teenager, trying to figure out "Is this my faith or not?" I remember meeting with the pastor a year or two after the accident and him saying, "You're taking your experience and you're sifting it through ... Everything that happens in the world is sifted through this accident. And what I encourage you to do is to go back and do that, identity, carving out your identity and figuring out 'Do I believe in Jesus? Do I believe in the Bible?' And then sift everything through the Word of God." And that was something I had to really intentionally do. Samuel Moore-Sobel(36:08): But I agree with you, I think it is toxic theology and I included it in the book not to call anybody out but I think to really say this is something that was really influential on how I've viewed myself, and I think, really, it's a call to action for all of us to influence ... We have to treat others, who've experienced trauma, in a better way. And saying that, having some of those theological discussions, the last thing I'll say to you, I think not only is it a distortion of the Word of God but I think that it also is ... Jumping in and having a theological discussion in a moment where I needed empathy, I needed people to just connect with me, but I just felt like when somebody just got through something really traumatic, that might not be the right ... Why are we casting about blame? Even if that's true, right? Samuel Moore-Sobel(36:51): And I will say, there are examples in the Bible where God does hold people accountable for the act of sinning that they're doing. You know the stories of David in the Psalms, right? And David and Bathsheba. And that's that situation, but that was not my situation. I was not doing anything wrong, I wasn't making a bomb, I wasn't doing anything with the sulfuric acid. I was literally helping other people. And so, it wasn't the fault of my parents, I wasn't actively sinning in that situation. Samuel Moore-Sobel(37:16): And so, I think there's this tendency in the Christian world where we just kind of have to assign that blame really quickly and I don't think it's healthy. And even if it was my fault, I don't think that's something you should tell somebody right out of the gate. I think you should empathize with people, then maybe there's room for those theological discussions down the road. But I totally agree, I think it is really toxic and I think influenced how people interacted with me and they weren't as empathetic because they assumed. Or there would be people who assumed I was doing something wrong in the situation or didn't want to hear the full story, and that was really hurtful too. Samuel Moore-Sobel(37:45): So, I think we just have to be really careful, especially as Christians, to interact in a loving way and not jump in and make these assumptions and start talking about why this happened. Ultimately, we don't know why it happened. I mean, there's no explanation for why a lot of these things happen and we just have to trust that God has a plan and keep moving. But it's not necessarily helpful to tell somebody that just a few months after a tragic accident. Stephanie Kostopoulos (38:08): Yeah. PSA, never tell anyone that ever. Beth Demme (38:10): Ever. Stephanie Kostopoulos (38:11): Ever. Beth Demme (38:12): It's not helpful. It's not helpful. In my opinion, it's not true. And it really stems from their discomfort and their wrestling, when in that moment their focus should have been on you. You were the one who was injured, as you're saying, you were the one who needed empathy and support, and it was just another example of people making it about themselves. Stephanie Kostopoulos (38:35): So, one of the things you've mentioned during this conversation is your emotional scars which, obviously, that's something that we talk a lot about on the podcast. So, you obviously had two big things with this. You had your physical scars and you had your emotional scars. So, I'm curious, as you were having surgery to improve your physical scars, did that improve your mental scars at all? And if so, if not, how did you even start to address the emotional scars of everything? Samuel Moore-Sobel(39:06): It was actually interesting because through the surgeries, it made it worse in some ways, because they were cutting up the same areas and opening up those old wounds, as it were, and the physical manifestation of that, and so I'd feel a lot of the same emotional feelings. I felt like I'd kind of go through this up and down valley of I'd finally come to a place of feeling like, "Okay, I'm able to kind of move forward and work through these emotional scars." And then, I'd have another surgery and it would kind of send me back down again, and I'd have to kind of re-grapple with all of those feelings and deal with the implications of everything that was happening all over again, which was frustrating at times. Samuel Moore-Sobel(39:43): I had my last surgery three years ago, and I could have had more, and made the decision not to and just to kind of leave it as is. And I don't know how that would be impacting me now, all these years later, if I was still going through surgeries and how that would have played out. But, for me, I went to a psychiatrist three months after the accident and that was really impactful to me because he introduced me to this concept of a toolbox and he talked about how important it was to have tools and be able to develop the tools necessary to combat some of the emotional scars and the feelings and the symptoms I was experiencing. And so, I was diagnosed with symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Pretty typical for undergoing a traumatic event like this. And so, kind of worked through those over several years. It was a long journey of counseling and all those tools. Samuel Moore-Sobel(40:35): So, one was counseling, the sessions I was having with my psychiatrist. The second tool was journaling, being able to journal about this experience, write about this experience, find the words to describe it. Another was talking to people that I trusted about this experience and being able to kind of have the sounding boards to be able to talk about it. Diet and exercise. There was also medication for a time. I was on vacation for a short time, to be able to kind of lessen the intensity of the symptoms that I was experiencing so I could deal with the root of the feelings. Samuel Moore-Sobel(41:06): And so, that was a really powerful metaphor for me, that I've carried with me ever since, and it's kind of the idea of ... He had kind of introduced that concept of depression being like a wave and you can see the wave on the horizon. And instead of getting knocked over by it when it hits you, you're able to withstand it by utilizing the tools that you have, so that you're able to kind of withstand whatever comes your way. And that was a really powerful metaphor that I've been able to hang on to ever since, and try to do that. Samuel Moore-Sobel(41:33): And the other thing I would emphasize is, because I've come a long way and don't experience the symptoms that I used to, but it's still a journey. Having good mental health, I think, is a daily journey sometimes, a weekly journey of kind of claiming that, and really waking up every morning and being determined. It's an intentional posture of saying, "I'm not going to go there today. I'm going to do these things, have these outlets to be able to work with whatever feelings come my way and keep moving forward," because it is something that you have to make that ... I think it's a choice and I think you have to make that choice. Samuel Moore-Sobel(42:05): And I'm just grateful that I had really good mental health ... Psychiatrist was not on the list of people who let me down, and was really great about helping me through this experience and giving me the tools. As he would say, I was the hero in my own story and so it was never him, but kind of helped me facilitate that healing that I think was really powerful. Beth Demme (42:22): I have been more aware since reading your book, I've been more aware of cultural references to burns like this. So, I don't know if you ever watched the show Jane The Virgin. Petra's mother is burned in the face with sulfuric acid. And sometimes I have read in the news about, in certain cultures, when families have to defend their honor, a girl might have sulfuric acid thrown on her face. Or, in an act of terrorism, in a market, someone might throw sulfuric acid on someone's face. How did those sit with you? Samuel Moore-Sobel(42:56): Yeah. What's troubling to me is that it is ... One of the things that I've seen before in a lot of these shows is kind of like that's the villain, has some sort of scar. You think of James Bond villains, you think of different ... Freddy Krueger, Scarface. There's this kind of cultural references where it's a negative. It's like, "Hey, they're bad if they have scars." Samuel Moore-Sobel(43:18): It's troubling to see that, because I'm kind of like, "Well, wait. I have scars, does that mean I'm a villain?" So that's something that I've had to think about and think about differently, and I think that it's just about having that sensitivity to other ... It's actually made me more sensitive to other things as well, like other people's ... who might be offended by other things. But you're right, it is something that I've struggled with, those cultural references. Samuel Moore-Sobel(43:40): In fact, there was an article ... The Phoenix Society for Burn Survivors is the largest burn survivor organization in the world and they talk about some of these things, and there was an article that they had pointed out about some of these things and how to kind of reframe that, and that was helpful. There are these references that are troubling and I wish it wasn't that way, because I think there's such beauty in scars. I think we all have, whether they are physical and emotional. A lot of us have kind of small physical scars that happen to us as we go through life. I just don't think the message that should be sent is that you're a villain or that it's just this nonchalant thing. Scars have beauty and they don't mean that you're a villain, they just mean that you're human. Samuel Moore-Sobel(44:17): I think scars help make us human and I think that there's great beauty in that experience. And it is odd to me sometimes how it's kind of just thrown into shows as kind of a minor subplot and left at that. Beth Demme (44:29): So, one of the things that you say in the book that I thought was such a profound and true statement is, you say, "I have learned through this experience that scars not only identify past struggle, but present triumph." So when we look at folks who have scars, and culturally or in media, or whatever, they're treated as villains, that's really not their real story. It's not the whole story, for sure. Because scars actually represent healing and it's like, "This shows you that I've been through something. I have endured. I have survived. I have overcome. Not just that I was wounded, but that I have overcome." Stephanie Kostopoulos (45:08): When we do attach it to the villain thing, I think we don't choose, necessarily, the scars that happened to us but we choose how to deal with those scars. And I think there are people that choose to be the victim and the villain, and then they ... "Well, I was treated badly so I'm going to treat everyone else badly," and those are those villains in those movies. And so, we get to choose how we are going to respond to the world, if we're going to take everything and say, "Everybody has wronged me because I was wronged in this situation." Stephanie Kostopoulos (45:41): And so, I think you have obviously turned it around and have not become the villain of the story, have become the hero and are showing us clearly that heroes have scars and you're strong and ... You've done the emotional work, I think that's a big thing. You can do the physical ... And, actually, as you were talking, I thought that was interesting, taking care of the physical scars actually brought in even more emotional scars, which actually makes sense as you were explaining that. But you were able to deal with your emotions and I think that's where the villains aren't. They aren't willing to deal with that emotional behind those scars. Samuel Moore-Sobel(46:21): Thank you so much. Yeah, it's important to have both and I think that the emotional piece sometimes isn't stressed enough in our culture. The doctors are really focused on the physical part and that's their job. But there's a whole other piece there, that just because you look okay or just because you look better than you did doesn't mean that you necessarily feel that way on the inside. And so, I think it's really important to have both. And I wasn't perfect, I made mistakes, and I write about that in the book. But I think, ultimately, I just was really determined to have a redemptive aspect to my story, and to just keep pushing and keep going, and there were so many heartbreaking moments but there were also some real mountaintop moments that I think ... it's helped make me who I am today, for better or for worse. Samuel Moore-Sobel(47:03): And I don't think I could have done anything to prevent the scars, like you said. It's a great point. It happened, but I can choose how to respond and I've tried to respond in this way. We all face adversity, we all have scars along the way, and it's the question of not so much if we will have scars but what we will do once they arrive. And so, I just encourage people to keep going. And for listeners out there who are having a hard time, especially during the pandemic, just keep going. Hopefully this inspires you today, but you can do it. You too can overcome and you too can make a difference. Stephanie Kostopoulos (47:38): Well, Samuel, we want to thank you so much for being on the show today. This was awesome, and you actually are the first guest that we've had that we don't know in person. We've never actually met. So, this is cool, this is fun. Because all of our guests have been people that we have known in some capacity. So, you're our first non-knowing person. But one day, maybe after the pandemic, we will meet you in person one day. Samuel Moore-Sobel(47:59): That would be awesome, I would love that. Beth Demme (48:02): So, we always like to ask our guests, what book TV show or podcast are you excited about right now? And, also, we want you to tell us where people can find you on social- Stephanie Kostopoulos (48:12): Not your address. [crosstalk 00:48:12] home address. Beth Demme (48:12): No, like social media. Samuel Moore-Sobel(48:14): My wife and I actually did, it was my first Audible book. She's introduced me to listening to books on Audible- Beth Demme (48:18): Audible. Samuel Moore-Sobel(48:18): ... which I was really hesitant to do at first. But, actually, it was really cool. We listened to Educated by Tara Westover. I know I'm a little late to the party, because it's been out for a while. But I mean, fantastic book and I think it really speaks to a lot of ... just scars, and coming of age, and working through ... separating from your parents, and believing what you need to believe, and working through the emotional scars and, in her case, physical scars too. There was a lot of really applicable things in there. It was cool to see that that book has done so well and that people have latched onto that story, because I think it's really powerful and it really changed my perspective on a lot of things. So, that's definitely a book that I really highly recommend and think was really fantastic. Beth Demme (48:58): And where can people find you on social media or ... ? Samuel Moore-Sobel(49:01): Yeah, absolutely. So, people can go to www.samuelmoore-sobel.com, M-O-O-R-E, hyphen, S-O-B-E-L. They can also find me on Twitter and Instagram @smoore_sobel. And then, also, if you want to buy the book, you can go to my website and find the purchase links or you can go directly to amazon.com and type in Can You See My Scars? or my name, Samuel Moore-Sobel. Beth Demme (49:25): And we'll have links to all of that in our show notes to make it easy for you. Stephanie Kostopoulos (49:27): It'll all be there. Stephanie Kostopoulos (49:30): At the end of each show, we end with Question for Reflection. These are questions based on today's show that Beth will read and leave a little pause between for you to answer it to yourself, or you can find a PDF on our Buy Me a Coffee page. Beth Demme (49:41): Number one, do you have any visible scars that make you self-conscious? Has Samuel's story made you look at your own scars differently? Number two, have you ever had to interact with someone who had major visible scarring? Has Samuel's story made you think about that interaction differently? Number three, do you have any emotional scars that make you self conscious? Where do they come from? And number four, have you ever thought about your physical or emotional scars as a punishment from God? Where did this unhealthy theology come from? Stephanie Kostopoulos (50:16): This has been the Discovering Our Scars Podcast. Thank you for joining us.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Meet StephMental Health Advocate. Author. Podcast Host. DIYer. Greyhound Mom. Meet BethI'm a mom who laughs a lot, mainly at myself. #UMC Pastor, recent Seminary grad, public speaker, blogger, and sometimes lawyer. Learning to #LiveLoved. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed